Nick Van Gilder

Posted 10/1/23

I’m Nick, a 4th year PhD candidate in the EEB department. A lifelong interest in amphibians and their conservation led me to move across the United States to work with Dr. Elizabeth Jockusch for my doctoral degree, in which I ironically study salamanders found in California! The landscape and dynamic climate of California have strongly shaped the diversification of salamanders in the region, especially those that lack lungs. Among the terrestrial vertebrates, lungless salamanders experience unique limitations on their activity because they need to stay wet to breath—yet most live entirely on land.

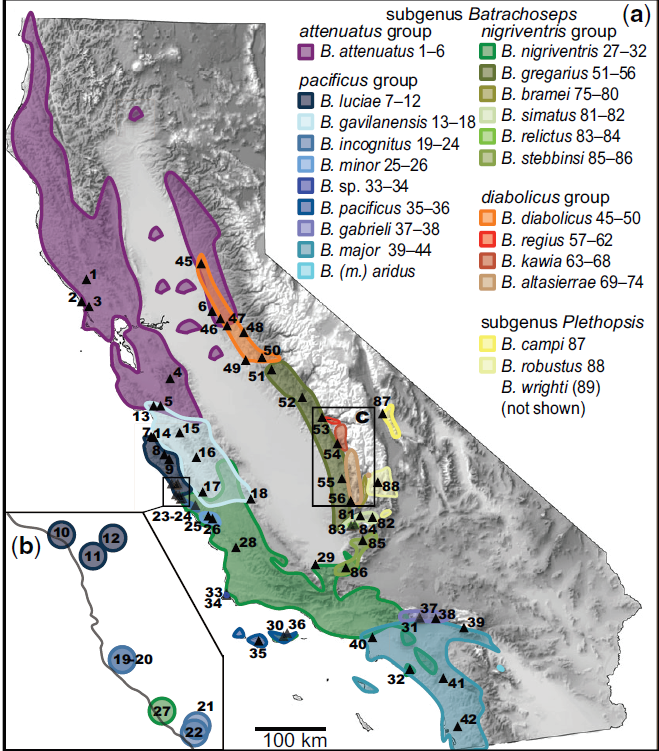

One diverse group of lungless salamanders found nearly exclusively in California are the slender salamanders, of the genus Batrachoseps. Though unassuming due to their size, these animals are remarkably adapted with long tails and slender bodies which allow them to persist underground while the surface habitat undergoes dramatic changes between seasons—from variably wet winters to consistently dry and scorching hot summers. Thanks to their adaptations, populations of these salamanders have persisted so long in enough places that they’ve diverged into an impressive 23 species, the most speciose group of salamander in the western US.

In my research, I use molecular approaches to inform the conservation and management of at-risk species and to characterize species diversity in the genus. In other words, I use DNA from the salamanders to answer questions about the status of their populations: are populations of a certain species sharing genes with one another, if so how often? How much genetic diversity is present in a given population of these salamanders? Are some groups of populations of salamanders divergent enough to be considered their own unique species?

To answer questions like these I spend a lot of time in the laboratory extracting and sequencing DNA samples, measuring and processing salamanders, and analyzing genetic data. But before I get to do the lab work, I have to get my hands on tissue samples from the salamander species of interest. Fieldwork for Batrachoseps has taken me to dense ravines in shrub-laden chaparral, up mountains to groves of massive sequoia trees, and to desert canyons crisscrossed with cold springs. My research has allowed me to both reconnect with landscapes in which I first spread my wings as a naturalist and has introduced me to new places beautiful beyond my comprehension.

Read more below to find out what it’s like to head into the field to find these salamanders!

The Incredible Inyos: April-May, 2021

Moving from California to Connecticut to study animals that live in California seemed like a puzzling decision, except for the fact that I was slated to work on a project beyond my wildest dreams: the conservation genetics of Batrachoseps campi, the Inyo Mountains Salamander.

While I had heard of these near-mythical, desert-dwelling salamanders prior to beginning graduate school, I spent nearly all my free time during the fall of 2020 and spring of 2021 reading everything I could about this species and the habitat that it occupies. The Inyo Mountains rise to just over 10,000ft in elevation in southeastern California, sitting between the eastern flank of the Sierra Nevada mountains and the arid Mojave Desert. It is within this peculiar habitat that these salamanders were first discovered in the early 1970s (Marlow et al. 1979), from a handful of canyons harboring cold springs where the salamanders can survive insulated from the harsh conditions on the surface.

More canyon populations were discovered soon thereafter, and early genetic work indicated highly diverged and separated populations across the mountain range (after all, this is a lungless salamander living in the desert!). A petition to list and formally protect this species via the Federal Endangered Species Act was proposed and submitted, and my research project planned to use modern genetic techniques to assess range-wide genetic diversity and population connectivity of this species to help determine whether or not this species required listing.

Though we had several samples on hand thanks to the dedicated efforts of our co-author and collaborator Dr. Christopher Norment (an emeritus vertebrate ecologist and esteemed author from SUNY Brockport), there were known sites for which we lacked our desired sample size. Thus, it was on a bright day in late April that I found myself hurtling down Interstate 5 in California’s Central Valley, headed southeast to the Inyos with my advisor Elizabeth. Our tiny rental SUV careened down the highway, turning the region that produces 25% of the United States’ domestic food supply into a mosaic of abstract green and brown shapes.

Eventually, we reached the southern terminus of the Central Valley near the city of Bakersfield and swung east along the Kern River Canyon into the southern Sierra Nevada. Suddenly I was in a brand-new place, but one that I had already gained brand-new perspective about thanks to my time in graduate school. The southern Sierra Nevada and the Kern River Canyon have long been a center of diversity for Batrachoseps: seven of the 23 species in the genus are found in the immediate vicinity of the river, or in the mountains surrounding the river canyon. As we climbed up canyon towards Lake Isabella, I yearned for conditions that would allow me to have seen some of the species whose habitats we passed (though, little did I know those conditions would come merely a week later—but that’s a story for another time!)

We reached the rural town of Lake Isabella and rewarded ourselves with delicious milkshakes from the locally renowned Nelda’s Diner, receiving suspicious glances from local patrons. Who were these strange people in a mix of field clothes and N95 masks? While the COVID pandemic was still in full swing at this point, residents of this quiet town seemed quite unconcerned, which sped up our milkshake drinking.

Finally ready to drive, we jumped back in the car for a final push out of the mountains and into the desert. Less than half an hour later, some oddly familiar shapes began to jump out at me from the roadside: weird, palm-like plants that looked almost like a candelabra were starting to dot the landscape. Elizabeth and I registered what these were simultaneously. Joshua Trees! Passing one of Southern California’s most well-known endemic plants was mind-boggling, and a fantastic reminder of just how far we had driven that day. However, reaching the desert floor at Highway 395 meant it was time to turn to the north, as the highways meet considerably south of the Inyo Mountains.

We raced the sunset to the north, trying to get to our planned campsite to meet up with Elizabeth’s longtime collaborator Robert Hansen and his friend Keith. After 500 miles on the road, we eventually pulled into the dusty patch of public land we had coordinates for and were relieved to see at least one of the two vehicles there occupied by a familiar face. After catching up with Bob and meeting Keith, another vehicle pulled up. In the driver’s seat of his trusty old Corolla sat Andrew Lorous, a US Geological Survey technician and good friend of mine (who I had met through a mutual love for slender salamanders!). We quickly set up camp and ate some food, and like clockwork I landed in my tent and shut my eyes. The day’s drive and sights whirred through my tired brain as I eagerly anticipated what morning light would bring—my first chance to search for Batrachoseps campi.

Salamander Search

I woke as the sun rose, shortly before 6am.

The dim light we pulled into camp with the night before had almost obscured the fact that we were camped directly beneath some of the tallest peaks of the Sierra Nevada, now illuminated by the sun emerging over the Inyos to our east.

We could almost see our destination for the day: one of the southernmost canyons in the range, where the salamanders are a unique brown color instead of their more common silver-frosted form. Bob was hoping to photograph a nice adult specimen for his upcoming field guide to the reptiles and amphibians of California, and we needed a few more tissue samples from this site, so within an hour we were being chauffeured over hardpan soil and gravel on the opposite side of the highway in a much more capable truck.

As we trekked across the desert, one of the most striking features of the landscape were enormous alluvial fans—the washed-out debris from flooding events—sitting at the mouth of every canyon we could see, in some cases protruding more than a mile out! The presence of these alluvial fans indicated periods of extreme volumes of water rushing down-canyon which made the alleged presence of salamanders in this range even crazier to me. Yet, even in this far-flung part of California I could see the human imprint on the hydrology of the region, most concretely when we drove over a crossing over the LA Aqueduct. This aqueduct is the lifeline of the Los Angeles basin, diverting water from the Owens River and Owens Valley Lake in order to support an ever-growing demand for agriculture, business, and municipal uses in Southern California (to read more about the dark history and human/ecological cost of this endeavor, click here).

Eventually, our route became rockier as we slowly trundled up the canyon. Looking out the window I was greeted by a sheer 15-foot drop, carved out by historic floodwaters. Upon reaching a dead end we parked the trucks, shouldered our bags, and began our walk up into the canyon. We passed stout Cottontop Cactus with pink-tinged spines, and spiny little Hedgehog Cacti adorned with scarlet blooms (two plants no salamander surveyor would ever expect to see while hoping to find salamanders!).

After a little while, we started to see a green, willow-studded draw that was likely being fed by a spring source—our first look at the actual habitat of this species. With little hesitation, I tore across the canyon bottom and wedged myself firmly under the willow branches and began to gently sift leaf litter and look under rocks, hoping to catch a glimpse of the salamander I’d dreamed of for over a year. I had soon exhausted the cover to look under, and it was about when I had come out of the willow thicket that I heard Elizabeth exclaim “OH, I GOT ONE!” from just upslope. I walked towards her as she revealed a chunky brown salamander in her outstretched hand.

This animal was big, with a broad head and a stocky frame—a far cry from the worm-like form that is typical for Batrachoseps. She handed me the salamander and there it sat in my hand, in full glory. As I looked down at it and across the Owens Valley at the snowcapped peak of Mt. Whitney my head was buzzing while my body was flooded with heart-pounding adrenaline. THIS was the moment I had been waiting for, for so long!

When I came back down to Earth from my cloud of salamander bliss it was time to get to work. Elizabeth’s animal was found under a rock adjacent to a gentle seep of cool water, not under the willow canopy at all. Changing my approach, I climbed higher up the canyon, stepping carefully around loose rock as the draw steepened. I reached a sheer face with water trickling down it, disappearing into a stand of grass at the base of the bedrock slab. In the grass lay a few sizeable stones, the first of which I turned to reveal my very own Batrachoseps!

This one was slightly larger than our first, and just as muted in coloration. A rock just feet over from the seeping water produced another salamander, a smaller juvenile this time. Juggling the salamanders was easier said than done, with one salamander kept moist and cool while I processed the other. In this case, processing the salamanders meant taking down GPS coordinates and habitat information, photographing them to scale with a ruler, and taking a small tissue sample from the end of the tail. From the tail tip, I would be able to extract ample DNA which would allow us to learn more about this population of salamanders for years to come. I thanked the salamanders for their contribution to science and bid them farewell under their rocks.

Success!

Zach Muscavitch

Posted 03/2023

I’m a 4th year PhD student at the University of Connecticut advised by Drs. Bernard Goffinet and Louise Lewis. I am an evolutionary biologist who studies lichens. Lichens are a symbiosis between a fungus and one or more algae. In this mutualistic symbiosis, algae photosynthesize and produce sugars for the lichen, while the fungi provide a complex structure to house the algae. The fungi also produce secondary compounds which may act to prevent herbivory and as a natural sunscreen. Lichens are very diverse with more than 20,000 described species of lichenized fungi (more than twice the number of birds!).

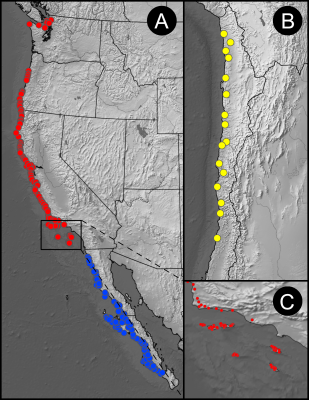

I’m particularly interested in the symbiosis between green algae and lichenized fungi. I use fog lichens (Niebla & Vermilacinia) and their algal symbiont Trebouxia as my study system. Many groups of lichens occur all around the world and are difficult to sample in a comprehensive manner, but this group is unique in that is only found in a narrow range along the Pacific coast of the Americas. I have previously done fieldwork in the US and Mexico and have extensive sampling of these species; however little is known about the species which occur in South America.

Prior to 1996, only about 15 species of fog lichens were known from North America, but detailed study of the group by Richard Spjut suggested 70 or more species. The lichens of the Atacama Desert have been poorly studied, with the majority of the few lichens collected here collected in the 1960s or earlier. Should fog lichens in the Atacama Desert receive scrutiny similar to Spjut’s collection efforts in the 1980s and 1990s, one might hypothesize a similar level of diversity in Chile.

Join me on my journey to Chile where I will spend 19 days in the Atacama Desert looking for fog lichens. I will fly from Connecticut, USA to Santiago, Chile. Then I will drive north to Iquique and slowly make my way south back to Santiago sampling along the way.

This work would not have been possible without the support of my good friends and mentors Bill Buck and Richard Harris.

Follow along with me on my journey in the Atacama Desert to find fog lichens below!

The Journey North

Day 1 – 20 February 2023

I arrived safely in Chile and I was fortunately able to avoid jet lag on my 9 hour flight by flying directly south. However, the time zones are a bit odd here. Despite being the same longitude as Connecticut, the time zone in Chile is two hours ahead of Eastern Standard Time. The upside of this was that at 7:30 AM (5:30AM EST), I had an amazing view of the sunrise over the snowcapped Andes as I landed in Santiago.

After clearing customs, I met Juan and Josefina and we began our journey north to the Atacama Desert. Juan is a Chilean bryologist who specializes in mosses and liverworts, he is especially eager to explore the northern Atacama Desert for mosses – yes, mosses really do grow in the driest desert in the world! Josefina studied seed dormancy for her PhD in many of the places we plan to visit in Northern Chile. These deserts may receive rainwater fewer than once in a decade. She’s also passionate about science communication, and has written some short books for children which integrate her experiences in the field.

Leaving the airport, we drove toward the coast. Santiago was relatively lush, with crops growing in the fields (as a native Wisconsinite, I instantly recognized cornfields from the car). As we left the Santiago Metropolitan region, we began traversing the coastal ranges via a winding road which eventually brought us to the coast. Here, I was delighted to find fog which persisted until mid-day. The road north primarily followed the coast, but turned toward the interior for brief portions when the coast became too topologically challenging for a road.

As we drove north, plants grew less abundant and eventually gave way to the more arid desert of Coquimbo. Here I saw a sign that immediately brought a smile to my face, “Precaución Zona de Niebla” (Warning Fog Zone in English). Niebla, or fog in Spanish, happens to be the scientific name of one of my fog lichens. I knew I was in the right place, and this would be a productive trip!

We finally stopped for the night in the small coastal town of Chañaral after driving ~1,000 km. I was very thankful to Juan for driving the whole way, and after 9 hours on the plane and ~ 11 hours in the car, I was very happy to stretch my legs and have a proper night’s sleep.

Day 2 – 21 February 2023

We started the day early and headed north. Today would be another long day of driving, but I had a couple thousand packets to fold for the weeks ahead which kept me busy. At the end of each day, I place each of the specimens I collect into their own numbered paper packet. The number corresponds to the locality (i.e., place name, latitude, longitude, elevation) I visited, information about the habitat (i.e., associated plants, type of soil, etc.), as well as the substrate the lichen grows on and the date. When I return to UConn and identify the material, I print a proper label and deposit it into UConn’s Herbarium.

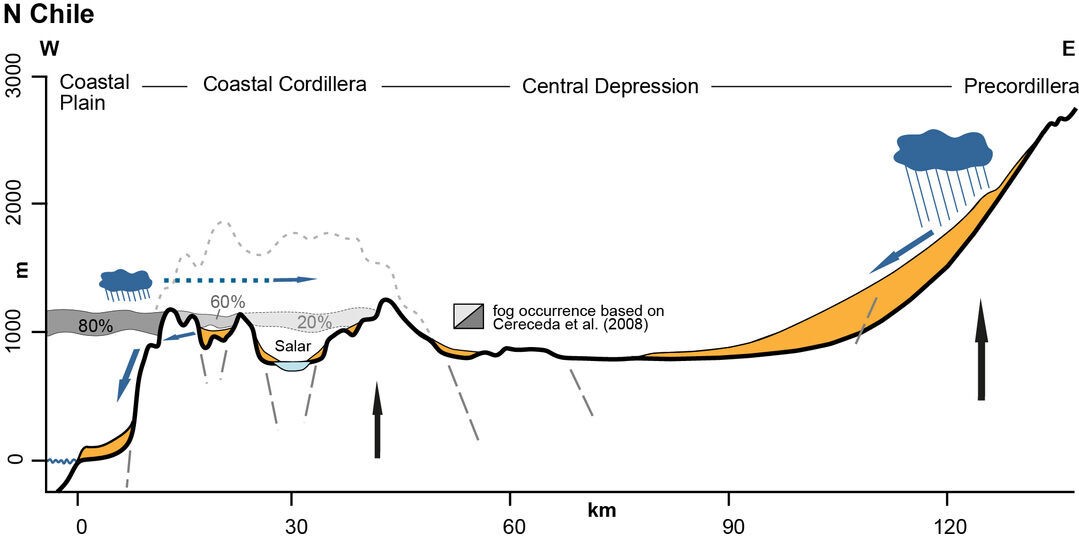

The road north from Chañaral was almost entirely coastal with a good view of the coastal ranges and the ocean. I saw fewer and fewer plants, and soon, the only plants I could see from the road were cacti and they were entirely restricted to the lomas, or fog oases, ~3,000 ft above the road.

From my car window, I could see large swaths of green along the side of the road, and on the western side of the lomas. This excited me, as I knew that these were lichens, even though Juan assured me that my lichens didn’t grow at the base of the lomas, they only grew near the top above 3,000 ft. After stopping on the side of the road to look at one of these sites filled with green ‘lichens’, I realized that the green color came from the rocks. This green color was either from serpentine soil, or from the copper in the rock. Copper is one of the main exports of Chile, and along the road, you could see evidence of mining operations everywhere. Unfortunately, I could no longer trust my eyes to spot lichens from the car with these deceptive green rocks everywhere.

Seeing these lomas so high above the road, I quickly realized that the fieldwork here would be much different from my fieldwork looking for fog lichens in North America. In the US and Mexico, the coast is much flatter, with the mountains further from the coast. In North America, the fog is low, and hugs the ground as it travels inland for 5 to 35 miles during the night and morning and condenses on the ground and the vegetation before the sun burns away the fog. In North America, I was able to do most of my sampling by the roadsides or climbing the relatively small mesas.

In Chile, the mountains occur right along the coast and prevent the fog from traveling very far inland. The fog bank is also much higher in Chile, and bathes only the tops of the westernmost parts of the mountains, while the interior receives nothing. Some areas in the Atacama Desert have never recorded any precipitation which is why this desert is the driest non-polar desert.

After a long day of traveling, we ended the day in Iquique. Our hotel was in the historic part of the city, and many of the original buildings had large front entrances made of wood – an exotic material for the desert without trees. Apparently, Iquique and other cities in the north were large exporters of nitrates used as fertilizer. Ships would leave Chile loaded with nitrate to be sent to the US and return to Chile with timber from the Pacific Northwest. The development of the Haber Process in 1913 destroyed this industry virtually overnight and many cities and towns were abandoned.

After dinner, we returned to our hotel. I was so excited about all the treasures I would find the next day that I was worried I wouldn’t be able to sleep, however after spending all day traveling in the car sleep came easy.

The Search Begins

Day 3 – 22 February 2023

Today was the day! I was finally going into the field to look for Chilean fog lichens! In the morning, we met Raquel Pinto. She is a local botanist who has devoted the last 50 years of her life to documenting and preserving the local fog oases and flora of northern Chile, and her expertise would be invaluable in the field. Many of the sites we planned to visit over the next few days were remote and only accessible via unmarked roads in the steep canyons. We never would have made it without Raquel as a guide. Raquel is truly the queen and protector of these northern fog oases.

The first site we visited was Alto Patache. Here I saw Cenozosia for the first time in the wild. I had seen only a specimen from the 1960s and from a collection by Daniel Stanton from 2020. Cenozosia is quite unique, as it’s hollow and rather spongy, but when dry it breaks very easily. When collecting it, I had to use a spray bottle to wet it so that it would stay intact. Cenozosia represents a sister linage to the fog lichens I focus on, but unlike Niebla and Vermilacinia, Cenozosia has only one species in the genus and is known only from the Atacama Desert. While one study suggests it to be the closest relative with my fog lichens, others suggest it may be more distantly related. I am excited to find out where it falls on the ‘lichen tree of life’, and which algae it associates with.

A little to the south, I was very excited to find sand. Here, in the sand dunes, I found a vagrant species of Niebla. One species had a morphology similar to caltrops, and the lichens would link together with each other. When linked together, they seemed to form terraces, where one thallus would occasionally come loose in the wind and would be transferred to a higher or lower terrace. This locality is the only site which still contains Santessonia cervicornis, as it seems to have disappeared from sites where it was previously known. Now that I’m familiar with this species, I will keep my eyes peeled for it, and try to expand its known range. Unfortunately, I think similar sites with sand will be difficult to find, as this site is very special.

Day 4– 23 February 2023

Today we drove by the Salar Grande which is a big salt flat. We passed large trucks continually transporting salt to the coast for international export as road salt. The side of the road was so white with salt that spilled from the trucks that it looked like snow.

As we drove to visit other sites, we saw some geoglyphs on the side of the mountains. These artworks were used by the early indigenous people who would make passage from the highlands in the Andes to the coast to get seafood. The image on the left appears to show a pyramid or temple. If you look closely, you can make out metal stakes in the ground which are there to discourage dune buggies and dirt bikes from damaging these ancient earthworks. In the image on the right, you can see a guanaco. Guanacos are an ancestor to the llama but are not domesticated. The sides of some of the mountains have trails which switchback up their sides, and these are remnants of the paths the guanacos used when they lived here. Unfortunately, the guanacos have not been seen in coastal Tarapacá for about 150 years, they are only found in the highlands now in the Northern regions of Chile. It's unclear how old these geoglyphs are - because of the scarcity of rain, and thus erosion from water, they may be multiple hundreds of years old.

We visited many Tillandsia sites today. Here the Tillandsia grow right on the ground as there aren’t large plants for them to grow on as epiphytes. The Tillandsia grow in linear mats which form terraces that ring the hillsides they are found on. Many of these Tillandsia sites are so extensive you can identify them from satellite maps. Raquel has written a book on the local flora and knows where all the sites are. Tillandsia are annual plants, and some sites have plants every year, while others may appear once every few decades depending on rainfall. While many of the Tillandsia sites have fog lichens, all of the Tillandsia sites seem to be found more interior, where the fog lichen diversity is not as rich.

We pitched our tents for a second night and Juan cooked us a dinner of tuna, rice, and carrots. As the desert cooled off, the wind slowed and we had a peaceful evening under the bright desert sky. The stars are much different in the southern hemisphere, and Juan and Josefina showed me how to find due south with the southern crosses in the night sky. We also had an excellent view of Jupiter, Mars, and Venus.

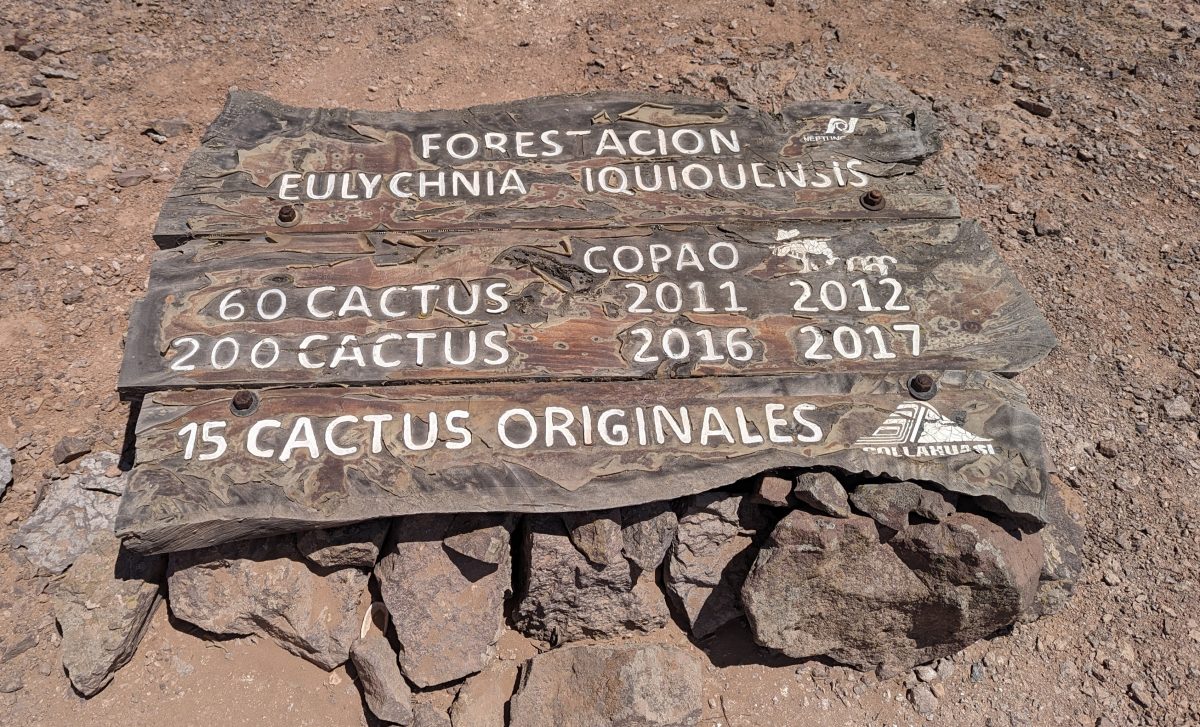

Day 5– 24 February 2023

Today was the last day in the field with Raquel. At 72 years of age, she struck an imposing example. She greeted us each morning with an exuberant smile and a resounding “buen día!” After a breakfast of eggs in the field, we journeyed north to a very special site. Raquel and her husband Arturo have restored a fog oasis with the indigenous cacti (Eulychnia iquiquensis). Raquel harvested the cactus fruits, processed the seeds, and planted them in a greenhouse in her home. She lovingly tended the seedlings and when they were strong enough, she and Atruro transplanted them into Punta Gruesa. What started out as 15 original cacti has grown to more than 200. To supplement them, fog nets (black mesh where the fog condenses) were installed to increase the moisture these cacti received.

In her more than 50 years of observing these fog oases, Raquel has noted that the fog oases are receding. Others have noted that the fog bank seems to climb higher, and less of the moisture condenses on these fog oases. These shifts in fog regimes may be exacerbated by climate change. Several of the sites had many dead cacti, with no signs of recruitment of younger cacti. The cacti grow so slowly that Raquel thinks some of the older ones with trunks more than a foot in diameter may be more than 1,000 years old. Unfortunately, since cacti don’t produce wood, you cannot core them to estimate their age. Raquel and Arturo’s work is so important because without propagation, these plants may go extinct, and so too would the mosses and lichens which rely on them as a substrate.

We helped Raquel harvest some of the cactus fruits. They are about the size of a racquet ball and are covered in one-centimeter-long white hairs. I was nervous to touch them, but after coaxing from Raquel I did and they were quite soft. One of the very ripe fruits had split open and Raquel had us all try some. It was slimy and a little tart with tiny black seeds. If the fruits were a little younger, they would have been more like a dragon fruit.

Juan was especially happy at this site, as he found one cactus with a collection of six mosses at the base. It’s good that he’s not relying on my eyes to find the mosses, as I collected several lichens from this cactus and didn’t notice. The Bryophytes here hide in deep crevices in the rocks, and they may only stick up 1-2 mm above the soil. Their leaves are also often red, orange, or a deep purple/black when dried, so they blend into the soil communities.

Before dinner, we walked along the seashore in Iquique. The tide was going out and I was able to visit the tide pools. Growing up in the Midwest, I didn’t have much opportunity to experience marine animals. In the pools there were a few different species of sea urchins whose spines were less dangerous than I expected. There were many anemones, and some were green which might mean they have photosynthetic algal symbionts. Most interesting to me however were the starfish. In Chile they are know as ‘sea suns’ (sol de mar) because starfish can have more than five arms unlike a traditional star. I was able to pick one of the sea suns and hold it in my hand while its small tube feet clung to my skin. The most unique thing I saw was a chiton. While I learned of this mollusk with eight plates, I had never seen one other than as a photo in a textbook.

I wasn’t able to make much progress processing my specimens as we spent the last two nights camping in the field, so I spent much of the evening processing my specimens before bed.